Russia’s Diplomatic Gambit in the Arctic

For much of the post–Cold War era, the Arctic was hailed as a zone of cooperation. Even adversaries found common ground on search and rescue, fisheries, and scientific monitoring in a region where survival demands collaboration. That consensus has fractured.

For much of the post–Cold War era, the Arctic was hailed as a zone of cooperation. Even adversaries found common ground on search and rescue, fisheries, and scientific monitoring in a region where survival demands collaboration. That consensus has fractured. At the center of the disruption is Russia, which now treats Arctic diplomacy not as a platform for shared stewardship, but as a stage to counter its isolation, secure partners, and project power.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 triggered its effective suspension from many Western-led forums, including the Arctic Council. Yet Moscow understands that being shut out of Arctic governance undermines its credibility as the state with the longest Arctic coastline. Its response has been to double down on symbolic diplomacy: hosting its own conferences, citing the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and positioning itself as a “responsible Arctic power.” These gestures are less about cooperation than about maintaining the appearance of legitimacy.

Perhaps the most consequential diplomatic move has been Russia’s embrace of China in the Arctic. Branding Beijing a “near-Arctic” partner, Moscow has welcomed Chinese capital and political cover into projects like Arctic LNG 2 and into discussions of Northern Sea Route access. For Russia, China’s involvement offsets Western sanctions and validates its claim that it is not isolated. For China, the partnership provides both energy security and a foothold in a region once considered closed to non-Arctic states. Together, they present a challenge to the Western vision of Arctic governance.

Even as it tilts toward China, Russia has not abandoned limited engagement with the West. It continues to participate in pragmatic forums such as the Arctic Coast Guard Forum, where cooperation on search-and-rescue and oil-spill response remains mutually beneficial. By keeping one foot in cooperative institutions, Russia signals that it can still be a partner when it chooses. This selective diplomacy becomes a bargaining chip: Moscow uses cooperation in the Arctic as leverage in wider geopolitical negotiations.

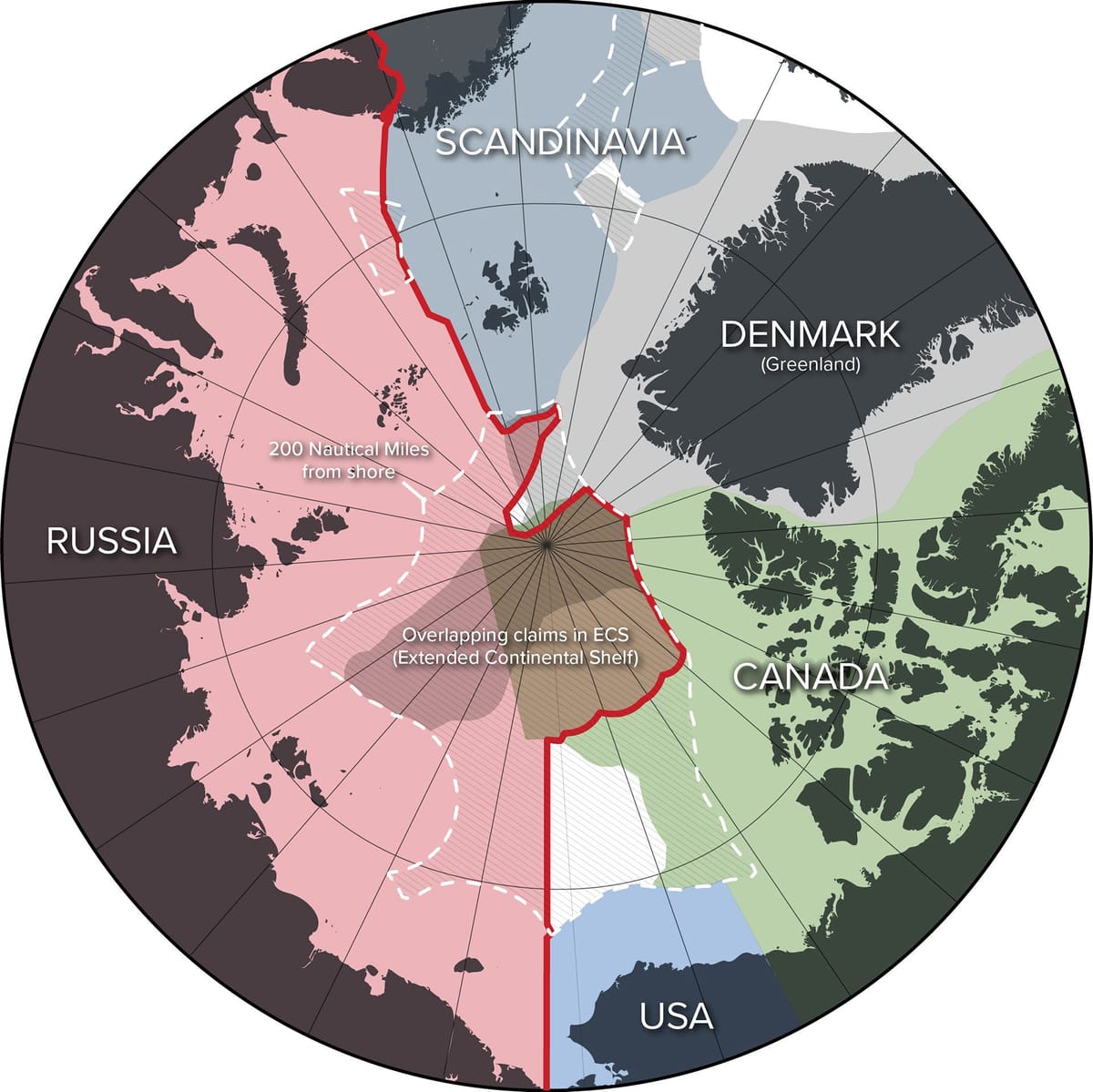

Diplomacy in the Arctic is not only about treaties and forums; it is also about symbols. Russia’s 2007 planting of a titanium flag on the seabed at the North Pole remains emblematic of its approach: bold, theatrical, and designed to force recognition of its claims. Its ongoing UNCLOS submissions for extended continental shelf rights serve the same function—whether or not they succeed, they assert Russia’s role as the indispensable Arctic actor.

The net result of these maneuvers is the unraveling of the so-called “Arctic consensus.” What was once a space of pragmatic collaboration is now a theater of managed confrontation. By combining symbolic gestures, selective cooperation, and a deepening alliance with China, Russia has transformed Arctic diplomacy into a tool of global strategy. Rather than a zone of peace, the Arctic increasingly reflects the fractures of the broader international system.

In the end, the Arctic is more than ice, resources, or shipping lanes. It is a mirror of Russia’s broader foreign policy: part performance, part pragmatism, and entirely strategic. By reframing diplomacy in the region, Moscow seeks not only to secure its northern frontier but also to rewrite the rules of engagement with the world.